The first question in a ruling by the Michigan Supreme Court is this: did it go beyond reason to put what the majority saw as the rights of incarcerated parents ahead of those of their children?

The second is with what effect and at what cost?

When the Michigan Supreme Court decided to hear In re Mason, it set in motion a sequence that has resulted in what administrators at the Department of Human Services called profound and immediate practice changes” in the ways that case workers now have to undertake dealings with incarcerated parents.

This ruling is one of the biggest things that’s happened to the field in recent history,” said Tobin Miller, Office of Legal Services at DHS.

This case came because the Macomb County Circuit court acted on a DHS petition to terminate the parental rights of a father, Richard Mason, who was in prison. The mother’s parental rights also had been terminated, but without contest.

The futures of two young boys, two and four years old, were at stake. The question was whether DHS denied due process to the father. Had then the circuit court and the Michigan Court of Appeals judges who ruled that the children were better off out of the custody of the imprisoned father also erred?

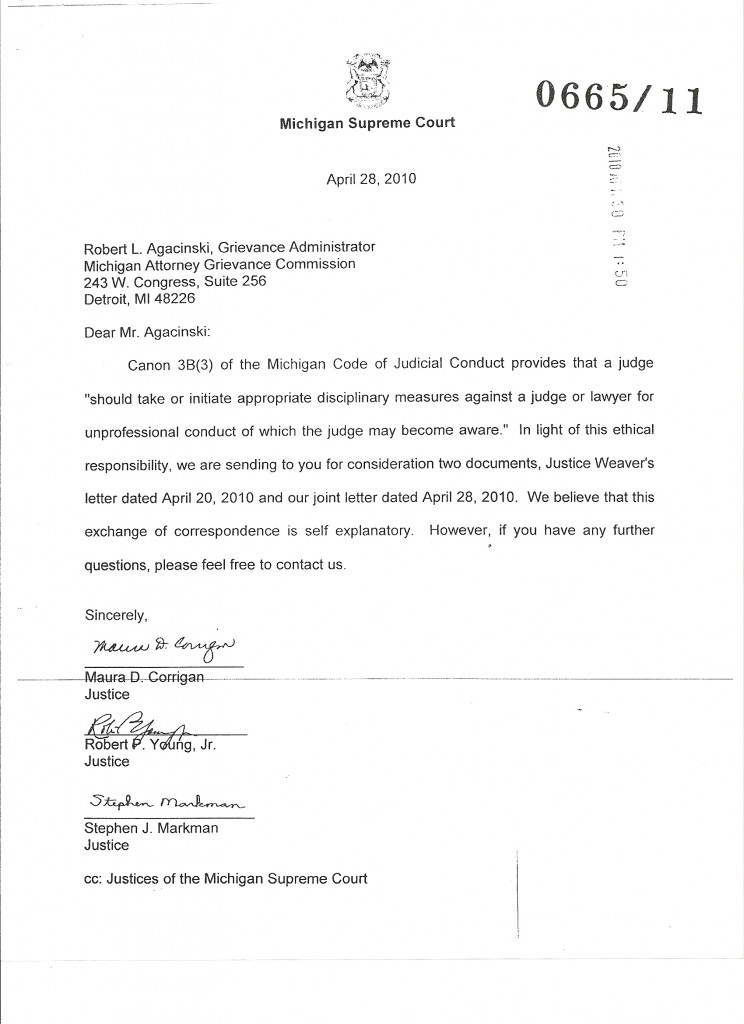

The court majority, including this time Justices Maura Corrigan (she is author of the majority opinion), Robert Preston Young, Jr., then-Chief Justice Marilyn Kelly, and Michael Cavanagh, said May 26, 2010, that the DHS worker had improperly done his work. In particular, even though his attorney was present during the court proceedings, the father was not on the phone as was his right under MCR 2.004. Nor was he offered a DHS Service Plan. And finally, the court ruled that a parent’s incarceration is not grounds for termination.

That was based on the majority’s understanding of MCL 712.A.19b (3)(h). The statute reads, in part:

(3) The court may terminate a parent’s parental rights to a child if the court finds, by clear and convincing evidence, 1 or more of the following:

[…]

(h) The parent is imprisoned for such a period that the child will be deprived of a normal home for a period exceeding 2 years, and the parent has not provided for the child’s proper care and custody, and there is no reasonable expectation that the parent will be able to provide proper care and custody within a reasonable time considering the child’s age.

Before Mason first we’d look at how long a parent would be incarcerated,” said Miller. And if that period would be greater than two years then we would not offer that parent a service plan…that is, arrange for services that would allow that parent to be reunified with that child [or children] at the end of incarceration.”

And if the parent was going to be incarceration for two years or more, said Miller, parental rights could be terminated.”

So, the majority reversed the findings of the Court of Appeals that upheld the Circuit Court that upheld DHS’ actions, the actions of casework Steven Haag (more about him presently).

The majority opinion is 26 pages. Writing the primary dissenting opinion, Justice Stephen Markman asserted that the father’s right of due process was untrammeled. This is the way he put it, siding with the lower courts:

I simply cannot support the majority’s conclusion that the trial court clearly erred by terminating respondent’s parental rights. In addition, given that respondent received all the process to which he was entitled under the law, I find no due process” violation in the fact that the majority is able to identify ways in which he could have been given still more process. The majority, quoting the children’s lawyer-guardian ad litem, asserts that respondent was ‘hamstrung from the beginning [in] trying to get things in order so that he [could] one day be a father to these children.’” However, the majority disregards two quite significant points. First, to the extent that respondent was hamstrung,” this was of his own making– nobody but respondent can be blamed for the fact that he was in prison during the pendency of these proceedings. Second, there is no evidence that respondent did anything to provide for his children while they were living with their unfit mother, with foster parents, or with their paternal aunt and uncle. Instead, respondent pleaded ‘no contest’ to the removal petition that alleged that Mr. Mason has failed to provide for the children physically, emotionally and financially.” Indeed, although respondent knew that the children’s mother was drinking again even before the court did, he still did nothing to try to protect his children from the precarious situation in which this placed his children. In addition, when he knew that his children were being removed from their mother, he did nothing to prevent them from being placed in foster care even though he had relatives who were willing and able to care for the children.

Despite respondent’s repeated failures in these regards, the majority reverses the judgment of the Court of Appeals, which affirmed the trial court’s termination of his parental rights, on the basis that the Department of Human Services (DHS) and the trial court did not do enough to help respondent become a better parent. I believe that the majority has it exactly backwards–respondent is the one who did not do enough to become a better parent. He did virtually nothing to demonstrate that he was willing or able to take responsibility for the care and custody of these children. It is potentially catastrophic for these children that their interest in a safe, secure, and stable home must again be placed in abeyance while respondent is afforded yet another opportunity to become a minimally acceptable parent.

Further, he warned the High Court against playing favorites:

Although the majority is certainly correct that an imprisoned parent is entitled to equal rights under the law, he is not entitled to special, and more favorable, consideration on account of this status.

He was joined in his opinion by Justice Diane Hathaway.

Justice Elizabeth A. Weaver (since retired from the Court) also agreed but took her dissent a step further:

The clear error in this case is not the Court of Appeals’ unanimous decision affirming the termination of the imprisoned father’s parental rights or the trial court’s decision to do so. The clear error is the Supreme Court majority’s unrestrained reaching out and the creation of an issue that was not raised in the trial court or the Court of Appeals and that takes 26 pages to find clear error by the trial court where there is none, with the tragic result for these two little boys, two and four years old, who will be deprived of the only parents they have ever known and the security of a stable and loving home that they so need and deserve. Indeed, the majority’s decision and opinion clearly and tragically have this case backwards.”

There was no judicial restraint in this case,” said Justice Weaver. There is no common sense to what the Justice Corrigan’s majority and opinion did. The four-vote majority put the interests of an imprisoned father above those of his children when it’s not clear in the law to do so. The majority court has gone beyond the statute.”

The result is things were going to change. And the way things had been done could not be the way they would be done in the future.

The implications are very broad,” said Cass County Probate Judge Susan Dobrich. She is past president of the Michigan Probate Judges Association, a group that takes positions on matters that come before its courts. I think historically it does reflect that we didn’t do a good job locating our fathers early on in cases. That’s what led up to it.”

And it’s mostly fathers in prison that we’re discussing here, she clarified. In Michigan we have a court rule that required judges allow fathers to have access to hearings by telephone. If you read Mason, some courts were not meeting the requirements. On first blush people will see due process issues.”

That doesn’t mean she favors the opinion.

Read the dissent by [Justice] Markman. He’s a good writer and he outlines the problems the ruling will raise.

The ruling certainly expands an already overburdened system. We did not do a good job engaging dads, but the question is did we swing the pendulum way far over on the other side. From my perspective, Markman’s dissent is where I’m at.”

Further, she said, the Court’s opinion is imprecise: I think the Court could have addressed the issue of services to be provided, but could have left it with more clarity for what we’re supposed to do.”

So, with no leadership (yet) from the legislature and an imprecise ruling from the Court, the Department of Human Services went to work to try to figure out what it needed to do to abide by the ruling of the Court. By September 17, administrators had drafted an initial response noting:

Since the Mason decision was issued, the Michigan Court of Appeals has reversed several orders terminating the parental rights of incarcerated parents and remanded the cases to the trial courts for further proceedings.

[…]

In all cases–whether a termination of parental rights order has been reversed or the case is ongoing–the following practice changes must be implemented immediately.

Then it went on to lay out the new procedures. …A lot of new procedures. Henceforth, incarcerated custodial parents had to be available by phone to take part in all matters pertaining to their custody; it wasn’t enough that their attorneys do it. If they were incarcerated in the same county as the court, the court may have them delivered to the hearings using writs of habeas corpus.

And the telephone hookup was not just court hearings, but all additional conferences, too, such as Permanency Planning Hearings.

Further, the foster care worker must attempt to engage incarcerated parents in developing a case service plan. This requirement applies regardless of the length of the parent’s incarceration.

One of the most chilling statements from the memorandum was this: the Michigan Court of Appeals has reversed several orders terminating the parental rights of incarcerated parents and remanded the cases to the trial courts for further proceedings.

What does that mean?

Quite a few custody cases have been reversed, a significant number…13 or 14. And that’s since May,” said Judge Susan Dobrich. It’s now the law and all the courts are following it.”

DHS’ Tobin Miller, double checked the number and confirmed: I believe 13 cases have been reversed…13 reversals of terminations based on Mason.”

That doesn’t mean that adoptions have been reversed, but it could involve pre-adoptive planning and placement.

You would never have the situation that an adoption was finalized and then an order reversing termination of parental rights,” said Miller. Michigan law says you cannot finalize an adoption [until all appeals have run]. You can have a child placed in a home and everything proceeding toward adoption and then have it terminated. In that case the plan is undone.”

So, if there were 13 cases of custody reversed, what’s the larger universe? How many incarcerated parents are we talking about?

We don’t have a good idea about that,” said Miller. There is no way to query our computer system. We draw our information from our SWSS (Service Workers Support System) and you can only draw out certain categories of information from the system. There is no way to ask the computer to tell us how many people are incarcerated in these cases. I wouldn’t even want to hazard a guess. It’s a fairly frequent occurrence, but as a percentage, I just don’t know.”

And is there any idea of the numbers of children?

There’s no way to tell,” he said.

Nor does the Michigan Department of Corrections have any idea. Richard Stapleton, Administrator with the Office of Legal Affairs, CAN tell us there are 43,900 prisoners now in the Michigan system. That’s down about a thousand from last year.

We don’t know how many have children who might be affected,” Stapleton said. We may have the data available…but I suspect not. Anecdotally, I think there are a good number of children of incarcerated parents. The average age of the prison population is somewhere in their 20s. And if they’re that age they are likely to have young children. Now, how many involved in parental rights’ terminations? Not all that many. I would guess not terribly many, maybe several thousand.”

Several thousand.

Judge Dobrich notes the ruling leaves DHS responsible for the cooperation of the Department of Corrections.

And it’s not just access to hearings and planning sessions. There is to be substantive education for the incarceration parent. What services will Department of Corrections provide that will meet the needs of parenting?” asked Judge Dobrich. It’s one thing to say ‘Take a parenting class in prison.’ Just because you pass it doesn’t make you a good parent. We’re going to need evidence-based programs with appropriate outcomes. And the only agency that can provide the service is the DOC.

Our dads who are in prison often are put on waiting lists for programming, and that requires more work on the case worker. We do want to engage the fathers but it’s difficult when in they are in prison.”

The longer the fathers have to wait, the longer it takes to make any assessments, to make determinations. Somebody very important is left waiting, says Dobrich: How long do these children have to wait because DOC isn’t going to provide the services we want?”

The Mason decision makes it clear that the length of the parent’s incarceration doesn’t necessarily play into the equation. How much can we do when they are in prison for a substantial time?” asks Judge Dobrich. And does this give more rights to the person in prison than the custodial parent who is not in prison?”

Another aspect of the decision was the determination that mere criminality cannot be a basis for termination. But [Justice] Markman said the reason the individual is in prison should be relevant. But how relevant? There needs to be more clarity.

Philosophically, the [Mason] decision makes a whole bunch of sense but how are the services going to be delivered?”

The ruling, said DHS’ Tobin Miller, adds difficulty to an already difficult task: So, after Mason, we said ‘Okay we have to offer reunification services for those incarcerated longer than two years.’

That means we have to treat incarcerated parents just like any other parents: we need to formulate a plan to get those services to them so they’ll be a prepared when the time comes [for them to get out].

It extends what case workers do now for non-incarcerated parents. It is much more difficult. You can’t just walk into a prison and say ‘I’m a caseworker and I am here to talk to a parent….’

We make contact by mail or telephone. We try to identify the services a parent needs and resources available in the prison to the parent. That’s difficult because services in DOC are limited and often the types of services the parent will need to be made whole, to be a good parent, are not available until parent approaches the out date. DOC says unless you are within six months, you’re not eligible for certain services, so case worker has to work within strictures of DOC.”

For the DOC, Richard Stapleton says there’s not a lot more work: I remember reading this [the decision] and thinking ‘Oh, shoot, what do we have to do now?’ As it worked out, not too much. The impact is minimal for corrections,” he said. We met not long after the case with DHS. All corrections has to do [in addition to what it already is doing] is facilitate communication between the prisoner and the court. We’ve agreed to get prisoners to the phones–and most of these will be by phone. A lot of the work can be done by mail. There is very little impact even by our staff being involved or even needing to know what’s occurring.

But there’s a lot of work for DHS.”

DHS’ Tobin Miller confirmed the meetings: We work with them [DOC]. We’ve done a couple of presentations and I’ve met with them, but we don’t have any direct control. That’s the tough part of this. If we could just say to DOC ‘The rules you have regarding types of service or when they’re available to prisoners are going to have to be changed’ our lives would be a whole lot easier. But we can’t. And I don’t think the DOC has the ability to do that anyway.

More confusing, posits Judge Dobrich, what happens in cases out of state? How does DHS compel another state’s prison to meet the dictates of the Michigan Supreme Court? What do we do if father is in Arizona?” she asks.

We have no control whatsoever,” says Miller of our-of-state incarcerations. And the problems with out-of-state prisoners are compounded. […] In Michigan you have a court rule that requires a prisoner within MDOC to participate by telephone in all proceedings. Outside of Michigan that court rule does not apply. And you have the added problem getting in touch with the prisoner. With regard to our communication with that prisoner there are different rules different states. And if that person is in a jail as opposed to a prison, it can be extremely difficult to get to the prisoner…there’s often no telephone. They’re just holding people. There is no way for us to contact them. Those things make it all the harder in those cases.”

But does that obviate the obligation imposed by the Court through Mason?

No.

All we can do is work within Mason,” said Miller. In those cases where there are no relevant services available to the prisoner some courts have been getting a psychological portrait of the parent. Then the court would have at least some other grounds on which to base terminations. But Mason says you cannot terminate solely on the grounds of incarceration.

What this will do in many cases is put the department in the position of really having to evaluate closely alternatives to termination and adoptions. Guardianship is an alternative. You may have kids in juvenile guardianships […] for a fairly long time and you can’t get grounds for termination.

That is not necessarily a negative thing. But generally, we don’t like to say we’re going to put the child in the care of another person for the long term and maintain the parental relationship. That can be kind of warehousing the child for a long time. It will make us evaluate those things when we end up with a fairly young child placed in guardianship or with family.

Warehousing a child. So, it’s possible you might have a two year old who could be in guardianship for the next 16 years because the parent isn’t going to get out before the child ages out?

This is not ideal with young children,” said Miller.

The majority in delivering this ruling singled out the caseworker, Steven Haag. Is that unusual?

Well, generally,” said Miller, what they do is say ‘Once again the Department….’ Did they single him out? I’ll have to read the case again…[flipping pages]…he formulated a service plan. There was proof that he was complying with certain things. ‘Had never spoken with respondent parent’…‘didn’t comply with policy’…‘failures by case worker jeopardized federal funding’….

I’d have to look at case service plan and then talk to the case worker. Just because the opinion states it [criticism] doesn’t mean it’s an accurate description of what happened. The case service plan is supposed to contain efforts to contact people but case workers are overworked. Fairly often.”

Haag didn’t operate in a vacuum. DHS is nothing if not a bureaucracy, replete with forms, procedures, and supervisors. Does all this land on Haag? What about his supervisor?

It does fall to the supervisor,” said Miller. As a matter of practice case workers and supervisors are so busy that if the case workers can get some minimal notes down in the case files, and continue to service the case, and remember what they did…that’s what they do.

Being a foster worker is one emergency after another. By time a case gets up to appeals it’s a more or less reflection of the way the case was treated on paper. I think in Mason the Supreme Court was simply making a point in a forceful way that we weren’t fulfilling what they saw as our duties. It does seem a bit unfair in that way [to the case worker].”

But blame aside, correction by the Court is not unknown, says Miller: We have to try to interpret the various laws that govern us, and it was determined that we were incorrect. That happens quite frequently. We change our policies and that changes practice.”

Even though the judgment requires a substantial amount of work,” says Judge Dobrich, we’re following the ruling, taking it in stride, and obeying it.”

But is there some serious grumbling?

Judges always grumble, and then they get to work and move on,” she said.

DHS, Tobin Miller adds: There is a lot of grumbling about the decision including on my part because it opened up a new field of difficulties at a time when we have a list of them. Especially, it affects the trial courts. I guess we can see that we needed to change practice…but day to day, getting communication with that incarcerated parent so he or she can participate in hearings or conferences…. We grumble because they [the majority Supreme Court justices] don’t perceive just how difficult those things are for people who don’t have enough time.”

Is there any irony in that Justice Corrigan, who led the charge into this issue, now has to deal with it as the head of DHS?

Maura’s got it back, eh?” asked Stapleton of DOC.

She’ll see it from a different perspective,” theorized Judge Dobrich. She is going to see that dealing with the pragmatic part is very difficult.”

Where are the funds coming from for all this?” Justice Weaver wonders. The people of Michigan do not have infinite resources. In fact, there are fewer and fewer resources to try and get it right.

The majority created an issue that wasn’t there. It was reaching. By interpretation the majority created unneeded law. You’re dealing with nonsense, not common sense, don’t you understand?”